A great sign in Brauð & Co; my chocolate croissant with Hallgrímskirkja in the background

I take Jason to the The Icelandic Phallological Museum (aka "the penis museum") just so he can say he did it. I went last time I was in Iceland, and it was above ground, on a corner building in a busy area. It's since moved to a very nicely redone underground area. They have a cafe that specializes in penis-shaped waffles. We walk around the museum, and the combination of the wet specimen jars and sweet waffle smell is off-putting.

A field mouse baculum. A baculum, or "penis bone," is a bone in the penis of some mammals that aids in reproduction by giving the penis the requisite stiffness for penetration. It is not present in humans (okay so explain where we get the euphemism "boning" from, scientists!?)

Make no mistake—the exhibits are gross. The penises on display are mostly wet specimens—which is biological matter floating in isopropyl alcohol in a jar—and they're disgusting to look at. Picture lots of beige tubes gently floating in pickle jars and you get the gist. I accidentally start us going the wrong direction, so the last thing we see are the ungulate wieners and the first thing we see is a human man's wang. The donor had red hair, in case you were wondering. On our way out, I'll see the cafe's tip jar—which is a giant carved wooden cock-n-balls, says "just the tips."

Wrong way

After, we take a walking tour of the city called "Elves, Trolls, and Ghosts of Reykjavik," which are basically the most important things to me in any city. Our guide, Guðni, ends up being the most patient man I've ever met, because our group of only 6 tourists is 50% dumbasses. There's an older white man from California in our group, as well as two women (presumed elderly daughter and even more elderly mom) also from California, and all three of them are insufferable. The women spend time talking to one another and constantly say "What?" to Guðni when they invariably miss half of what he explains. The man is apparently trying to get an A+ in Annoying Tourist because whenever Guðni stops to draw breath, the man asks things like "Do cars cost a lot of money in Iceland? How much did your house cost? Okay, but are trolls really real?" At one point in the tour, Guðni has to say something like "That's a great question, but what I'd really like to talk about is this statue and story" to be able to continue the tour.

Our first stop on the tour is above a Viking settlement excavation, which is part of The Settlement Exhibition for the Reykjavík City Museum. It's a big glass box that rests on the sidewalk, which if you look down you see the excavation of a Viking settlement below. Guðni explains that the settlement is from the year 871...plus-or-minus 2 because the dating isn't exact. We see references to 871 +/- 2 everywhere, which makes me really happy: I love when museums are honest that they don't have all the answers, and are just working with the best information available to them at the time. Discovered during construction work in 2001, the settlement is the earliest evidence of human habitation in Reykjavík, and is a longhouse and collection of artifacts found right there on site.

The map

Next, our guide takes us to a huge topographical map inside a city building to give us the scope of Iceland. Turns out, it's about the size of Ohio. If you took every person who ever lived in Iceland from 871 (plus or minus 2) until now, you still wouldn't have a million people. Where Jason and I will visit this trip is a shallow C-shape made from the West Fjords (northwest), Reykjavík in the southwest, the Golden Circle, which is central-ish, and Vík in the south. Guðni points out Eyjafjallajökull, a volcano that famously erupted over a series of months in 2010, sending ash across Iceland and Europe. Later, I'll buy a vase from a ceramic artist who mixes ash from that eruption into her glaze, creating a dark speckle across her work.

Guðni continues our tour, leading us around a man-made pond and to a few public artworks. He tells us that when people first came to Iceland, the gods were tools to explain the natural phenomenon they were seeing. Lightning and thunder was the god Þór (Thor) riding across the heavens in his chariot. The Vikings and their descendants had a very personal relationship with the gods, who were talked to, sacrificed to, prayed to. When the Christianity came to Iceland in the year 1000, the Church of course banned worship of these old gods. Guðni shares that in many communities, the statues of Thor, Odin, and others were often cast into waterfalls to appease the clergy...but the farmers hid their statues of Frejya and Frigg and continued to worship them in secret. As Guðni put it "These were practical farmers. Worshiping their gods of fertility and harvest had done well so far...why change?"

Hallgrímskirkja in the distance; Hooper swans in the foreground

Guðni continues our tour, leading us around a man-made pond and to a few public artworks. He tells us that when people first came to Iceland, the gods were tools to explain the natural phenomenon they were seeing. Lightning and thunder was the god Þór (Thor) riding across the heavens in his chariot. The Vikings and their descendants had a very personal relationship with the gods, who were talked to, sacrificed to, prayed to. When the Christianity came to Iceland in the year 1000, the Church of course banned worship of these old gods. Guðni shares that in many communities, the statues of Thor, Odin, and others were often cast into waterfalls to appease the clergy...but the farmers hid their statues of Frejya and Frigg and continued to worship them in secret. As Guðni put it "These were practical farmers. Worshiping their gods of fertility and harvest had done well so far...why change?"

With Christianity, according to Guðni, came a rise in troll rhetoric. He explains that at this time in history, the Church began using stories of trolls as parables. In these stories, trolls represented the wicked wilds, and the people who outwitted them did so by following the new Christian doctrines. Jason and I will see trolls later in our trip: Reynisdrangar, the sea stacks off the coast of Vík, are trolls who stayed out too late and got caught by sun, which turned them to stone.

Domkirkjan, a small Lutheran church in downtown right next to the Althingishus (Parliament House)

Domkirkjan, a small Lutheran church in downtown right next to the Althingishus (Parliament House)

“The gods were to explain natural phenomenons, and the trolls were a tool of the church. But stories of the hidden folk, those were for the people,” shares Guðni. Huldufólkh—hidden people, or elves—were and continue to be a part of Icelandic life. Today, over half the population of Iceland reports they believe in elves or the possibility that elves exist. The hidden people may be an amalgamation of the elves/nature spirits of the Vikings and the fae/nature spirits of the enslaved Irish people that arrived in Iceland, although some researchers believe there remain two distinct entities. Regardless, hidden people are not like Victorian fairies—small beings the flit around like butterflies. The hidden folk of Iceland are human-looking magical beings that live in a parallel world but who can and do slip through the veil to live alongside us, helping or vexing people as they choose.

“Have you ever seen an elf?” interrupts the man at one point in Guðni’s talk. Guðni is taken aback, and seems reluctant to share his own story. “I have not seen them, but I have felt them,” he finally shares. “Oh yes, I’ve felt them!” says one of the women excitedly. “You can definitely feel them, it’s like…a feeling. Like a presence.” Her companion agrees, and the man talks with them as we continue our walk. I want to ask Guðni so many questions about his experience, but from his reaction I don’t think he wants to talk about it.

A small building in the center of the Old Churchyard

The last part of our tour is at Hólavallagarður, also called the Old Churchyard. It’s Reykjavik’s “new” cemetery, meaning it was established in the 1800s, not the Viking era. It’s a wonderfully peaceful spot, with mossy pathways dappled by the sun breaking through fall-brightened leaves. The sound of nearby traffic is drowned out by birdsong. Guðni weaves us around the plots, many blooming with heather, leading us to the small graif of Steinunn Sveinsdóttir.

More than two hundred years ago, Steinunn Sveinsdóttir and her husband, a farmer, purchased some land with some friends of theirs, another husband-and-wife pair. Eventually, after living and working together, Steinunn and the other man fell in love. Steinunn would profess to her dying day that she was not an accomplice to their murders, but as it happened the man killed Steinunn’s husband and his own wife. The pair was tried, and both sentenced to death. There was trouble in finding an executioner willing to carry out Steinunn’s sentence, however. Eventually tired of the delay, the local authorities found someone in Norway willing to do the killing, but before she could be sent off, Steinunn died in prison.

As a criminal, Steinunn was unable to be buried in the cemetery. Instead, her grave was a cain on the hill near present-day Hallgrímskirkja. As people walked past her grave, it became the custom to add another rock to her burial mound.

…until people began seeing Steinunn Sveinsdóttir again, that is. Steinunn was said to appear to people, sad, crying, forlorn. She said the weight of all these rocks was too heavy. She was innocent, and the burden was too much to bear. People began championing Steinunn’s innocence, requesting her verdict be overturned and her body laid to rest in the cemetery. Steinunn was eventually exhumed and reburied in the cemetery. Today, a small white cross marks her grave, and people leave angel figurines at her grave. Her ghost has not been seen since her reburial.

Steinunn's grave, marker erected in 2012

Possibly my favorite fact about Iceland relates to their graveyards: in Iceland, the first person buried in a graveyard is said to be its guardian. The guardian’s spirit protects all of the dead who are buried after them in their cemetery. Holavallagarour’s guardian, Guðrún Oddsdóttir, died in 1838. I think I would like to be a graveyard guardian.

“The gods were to explain natural phenomenons, and the trolls were a tool of the church. But stories of the hidden folk, those were for the people,” shares Guðni. Huldufólkh—hidden people, or elves—were and continue to be a part of Icelandic life. Today, over half the population of Iceland reports they believe in elves or the possibility that elves exist. The hidden people may be an amalgamation of the elves/nature spirits of the Vikings and the fae/nature spirits of the enslaved Irish people that arrived in Iceland, although some researchers believe there remain two distinct entities. Regardless, hidden people are not like Victorian fairies—small beings the flit around like butterflies. The hidden folk of Iceland are human-looking magical beings that live in a parallel world but who can and do slip through the veil to live alongside us, helping or vexing people as they choose.

“Have you ever seen an elf?” interrupts the man at one point in Guðni’s talk. Guðni is taken aback, and seems reluctant to share his own story. “I have not seen them, but I have felt them,” he finally shares. “Oh yes, I’ve felt them!” says one of the women excitedly. “You can definitely feel them, it’s like…a feeling. Like a presence.” Her companion agrees, and the man talks with them as we continue our walk. I want to ask Guðni so many questions about his experience, but from his reaction I don’t think he wants to talk about it.

A small building in the center of the Old Churchyard

The last part of our tour is at Hólavallagarður, also called the Old Churchyard. It’s Reykjavik’s “new” cemetery, meaning it was established in the 1800s, not the Viking era. It’s a wonderfully peaceful spot, with mossy pathways dappled by the sun breaking through fall-brightened leaves. The sound of nearby traffic is drowned out by birdsong. Guðni weaves us around the plots, many blooming with heather, leading us to the small graif of Steinunn Sveinsdóttir.

More than two hundred years ago, Steinunn Sveinsdóttir and her husband, a farmer, purchased some land with some friends of theirs, another husband-and-wife pair. Eventually, after living and working together, Steinunn and the other man fell in love. Steinunn would profess to her dying day that she was not an accomplice to their murders, but as it happened the man killed Steinunn’s husband and his own wife. The pair was tried, and both sentenced to death. There was trouble in finding an executioner willing to carry out Steinunn’s sentence, however. Eventually tired of the delay, the local authorities found someone in Norway willing to do the killing, but before she could be sent off, Steinunn died in prison.

As a criminal, Steinunn was unable to be buried in the cemetery. Instead, her grave was a cain on the hill near present-day Hallgrímskirkja. As people walked past her grave, it became the custom to add another rock to her burial mound.

…until people began seeing Steinunn Sveinsdóttir again, that is. Steinunn was said to appear to people, sad, crying, forlorn. She said the weight of all these rocks was too heavy. She was innocent, and the burden was too much to bear. People began championing Steinunn’s innocence, requesting her verdict be overturned and her body laid to rest in the cemetery. Steinunn was eventually exhumed and reburied in the cemetery. Today, a small white cross marks her grave, and people leave angel figurines at her grave. Her ghost has not been seen since her reburial.

Steinunn's grave, marker erected in 2012

Possibly my favorite fact about Iceland relates to their graveyards: in Iceland, the first person buried in a graveyard is said to be its guardian. The guardian’s spirit protects all of the dead who are buried after them in their cemetery. Holavallagarour’s guardian, Guðrún Oddsdóttir, died in 1838. I think I would like to be a graveyard guardian.

Plots in the Old Churchyard. When I die, I shall become a graveyard guardian

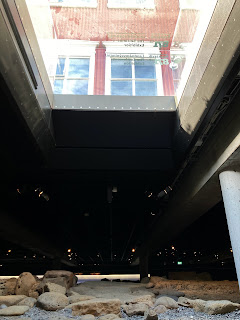

After the tour, Jason and I circle back to the Reykjavik City Museum to check out the Settlement Exhibition from the inside. We walk down a spiraling staircase, belowground where the exhibit begins. The museum was built around the 2001 find of this Viking longhouse. The museum has a really unusual setup. The ceilings are low (we are underground, afterall), and there is one skylight that lets in daylight from the street above (the glass box we peeked through on our tour). Some of the artifacts found at the site are in wall vitrines that surround the excavation site.

Jason and I experience museums very differently. He’s an information gatherer, reading almost every label and tag. Museum professionals like me love visitors like him, because they answer the “so what?” and “who cares?” about our jobs. Museum professionals are challenged by visitors like me, on the other hand, who flit from one item to another, ignoring chronology, linear storytelling, or methodology. I don’t remember dates or facts or figures in this exhibit. What I do remember is that by the bathrooms, some designer has included a mouse hole-sized cutout in the wall. An LED screen in the hole plays a video of a little mouse that scurrys back and forth, occasionally peering out at the viewers. I identify with this mouse.

The dug walkways make the longhouse excavation site at about chest-height. There is one skylight for daylight, and vitrines built in the walls around the excavation

There’s more museum, but it’s less interesting to me, mostly Reykjavik’s industrial history. I do like that the elevators have a label on them that says “time machine” (timavél in Icelandic) since by using them you skip from the Viking era to the 1900s. We take the spiraling staircase back up to street level and 2022.

Jason’s tired again, so I drop him off at the hotel and go back out to walk some more. I find a statue of a bear outside of a home. The marble base it sits on says BERLIN 2380 KM. I find graffiti that says SEXY GOBLIN 2019, a shop cat with a sign requesting visitors not disturb him while he’s sleeping (he asleep so I let him be), and an ice cream shop I want to try later. I swing by to get Jason, and we walk to the Reykjavik Fish Restaurant for dinner, and get pretty good fish and chips.

Jason and I experience museums very differently. He’s an information gatherer, reading almost every label and tag. Museum professionals like me love visitors like him, because they answer the “so what?” and “who cares?” about our jobs. Museum professionals are challenged by visitors like me, on the other hand, who flit from one item to another, ignoring chronology, linear storytelling, or methodology. I don’t remember dates or facts or figures in this exhibit. What I do remember is that by the bathrooms, some designer has included a mouse hole-sized cutout in the wall. An LED screen in the hole plays a video of a little mouse that scurrys back and forth, occasionally peering out at the viewers. I identify with this mouse.

The dug walkways make the longhouse excavation site at about chest-height. There is one skylight for daylight, and vitrines built in the walls around the excavation

There’s more museum, but it’s less interesting to me, mostly Reykjavik’s industrial history. I do like that the elevators have a label on them that says “time machine” (timavél in Icelandic) since by using them you skip from the Viking era to the 1900s. We take the spiraling staircase back up to street level and 2022.

Jason’s tired again, so I drop him off at the hotel and go back out to walk some more. I find a statue of a bear outside of a home. The marble base it sits on says BERLIN 2380 KM. I find graffiti that says SEXY GOBLIN 2019, a shop cat with a sign requesting visitors not disturb him while he’s sleeping (he asleep so I let him be), and an ice cream shop I want to try later. I swing by to get Jason, and we walk to the Reykjavik Fish Restaurant for dinner, and get pretty good fish and chips.

We decide to try Brennivín, Iceland’s signature liquor. It’s flavored with caraway, and I’ve heard it described as tasting like liquorice, like rye bread, and like herbs. Jason goes to the bar and orders it, but the woman behind the counter doesn’t understand him when he says “bren-A-vin.” She tries to teach us how to say it: emphasis on the first syllable, a rolled r, an indescribable Nordic-ness to her pronunciation. Jason will later read that in Icelandic, if you have to guess at how to pronounce something your best bet is to emphasize the first syllable. Another bartender, this one with long dark hair, comes up to us to pour the shots. So far, wait staff have been polite, but reserved. As she pours the shot, the glass overflows and her eyes get side. “I’m not a bartender!” she laughs, and the humanity of the moment is incredibly touching. She looks at us dubiously as we skål and take our shots. I make a face back at her as I swallow. “It’s horrible,” she agrees. “I hate it.” As this trip progresses, Jason will tell me this is one of his favorite memories of our whole trip.

We walk back to the hotel down the rainbow road, stopping to pet cats and people watch.